Is the Airbus A322 Feasible as the Future of Mid-Market Flying?

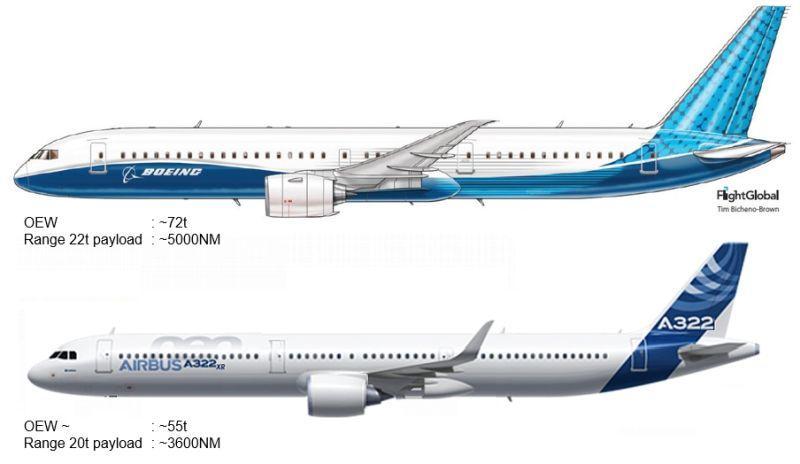

In the ever-changing landscape of commercial aviation, one of the most talked-about “what if” aircraft is the Airbus A322. Though never officially launched, the A322 has become a kind of unofficial placeholder for an airplane that could bridge the gap between high-capacity narrowbodies and small widebodies—a role once filled by the Boeing 757 and, to some extent, the 767-200. The concept is simple but ambitious: a single-aisle aircraft seating 220–250 passengers and flying about 3,800 nautical mile (7,000 km), combining the economics of a narrowbody with the range and comfort of a widebody.

The idea springs from the success of the A321neo, particularly the A321XLR. Airbus stretched the A321’s range to 4,700 nautical miles (around 8,700 km) and squeezed in up to 244 seats in a dense layout, proving airlines want more from single-aisles. The A322 would push further—adding four to five more rows, incorporating Airbus’s composite “Wings of Tomorrow” technology for greater lift and fuel efficiency, and pairing the airframe with upgraded engines such as next-generation LEAP or UltraFan derivatives. In theory, it would let airlines replace aging 757-300s, 767s, and even some 787s on thinner long-haul routes at lower trip costs.

Is the Airbus A322 Realistic?

Technically, this evolution is feasible. Airbus already has a strong engineering foundation in the A321XLR program and its composite wing initiatives. Stretching the fuselage, upgrading the wing, and reinforcing the landing gear are all within reach, albeit with careful design work to manage weight, bending stresses, and gate compatibility. It would not be a clean-sheet aircraft but a major derivative—a strategy Airbus has used successfully before.

Strategically, though, the A322 is far from certain. Airbus has not committed to launching it, and the middle of the market remains fragmented. Some airlines want more range, others want more seats, but few want both in a single-aisle format. The cost of development—even for a derivative—would be measured in billions. Yet compared with Boeing’s shelved New Midsize Airplane 797 project, an A322 could be a relatively low-risk way for Airbus to extend its lead.

If launched, the A322 could disrupt the “widebody-lite” market. It could allow airlines to connect secondary cities across oceans, offer better seat economics than current narrowbodies, and pressure Boeing to respond in a segment it once dominated. Boeing’s largest 737 MAX variant—the 737-10—is the closest competitor in size, but with a typical capacity of about 230 passengers and a much shorter range, around 3,400 nm (6,300 km), it targets high-density short-to-medium routes rather than true transatlantic missions. An A322 would leapfrog that capability with longer legs and potentially higher comfort levels.

For now, the A322 remains an aspirational concept—a compelling blend of market demand, technological evolution, and strategic opportunity. Whether it becomes reality or stays on the drawing board, it highlights a deeper truth about aviation: the future isn’t always built from scratch. Sometimes it’s stretched from success.

Despite persistent rumors, Airbus has confirmed there is no A322 launch program planned. Chief Commercial Officer Christian Scherer recently addressed the speculation directly, emphasizing that while an A322-style stretch has been studied internally, “there is no such thing” as an active A322 program. Instead of an incremental stretch of the A321neo family, Airbus is focusing its resources on a clean-sheet next-generation narrowbody aircraft. This new design, expected to incorporate advanced propulsion and composite technologies, is projected to enter service in the second half of the 2030s, signaling Airbus’s commitment to leapfrogging current designs rather than tweaking existing platforms.

Speculative Comparison Table — A322 vs. Key Rivals

| Aircraft (Speculative/Actual) | Typical Seating | Range (km) | Type | Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airbus A322 (concept) | 220–250 | ~3,800 nm (7,000 km) | Single-aisle (stretched A321XLR) | Middle-market, thin long-haul routes |

| Airbus A321XLR (in service 2024) | 206–244 | ~4,700 nm (8,700 km) | Single-aisle | Long-range narrowbody; transatlantic |

| Boeing 737-10 Max | ~188–230 | ~3,400 nm (6,300 km) | Single-aisle | High-density short/medium-haul routes |

| Boeing 757-200 and -300 (no longer produced) | ~200-243 | ~3,400-3,900 nm (6,300-7,250 km) | Single-aisle | Former mid-market staple |

| Boeing 797 NMA | 220-270 | ~4,500-5,000 nm (8,300-9,250 km) | Small Twin-aisle | Small twin-aisle or “hybrid” cross-section; long-haul, thin transoceanic routes |

Could a “787 Shrink” Replace the 737 and 757? Why the Dreamliner Blueprint Doesn’t Fit the Mission

Boeing’s narrowbody future is under intense scrutiny. With the 737 MAX still facing quality and regulatory challenges and the 757 long retired, speculation often resurfaces: why not “shrink” the 787 Dreamliner into a lighter, shorter-range jet to leapfrog a clean-sheet 737 replacement? On paper the idea looks elegant—reuse the Dreamliner’s advanced composite structure, modern systems, and global supply chain. In practice, both history and physics tell a different story.

The Precedent: 787-3 — Conceived, Then Canceled

Boeing has already attempted a short-range Dreamliner. The 787-3 was a high-capacity variant designed for Japan’s domestic market, sharing the 787-8 fuselage but de-rated for shorter routes and optimized for slot-constrained airports. It promised 290–330 seats with a 2,500–3,050 nm (4,600-5,650) range. Yet by 2010 the program was shelved as customers pivoted to the standard 787-8, citing economics that didn’t justify the variant. The lesson: even a purpose-built, “condensed” 787 struggled to make financial sense on short-haul operations. A “787 shrink” would inherit the same wrong DNA for one-to-three-hour missions where low weight, fast turn times, and narrowbody gate economics rule.

The Real 737/757 Successor Problem Boeing Is Trying to Solve

For nearly a decade Boeing studied the New Midsize Airplane (NMA or “797”)—a concept in the 220–270 seat, 4,500–5,000 nm (8,300-9,250 km) range bracket aimed at filling the gap between the 757 and 767 without dragging in widebody weight. Multiple credible reports described a small twin-aisle or “hybrid” cross-section, not a repurposed 787. Work stalled and was eventually shelved as Boeing prioritized cash preservation, dealt with the MAX crisis, and faced a tougher certification environment. Meanwhile, Airbus advanced by stretching the A321 family into the LR and XLR, proving that the middle market can be served by long-range single-aisles when the airframe is light and right-sized. That further undercut the rationale for a heavy “787-lite.”

Timing, Technology, and Why Boeing Keeps Saying “Not Yet”

Boeing leadership has repeatedly signaled there won’t be a clean-sheet airliner until the mid-2030s, insisting any new product must deliver a 20–30% step-change in economics—something likely requiring next-generation propulsion such as CFM’s open-fan RISE, which is targeting entry into service around 2035. Launching a new family too soon risks being stranded by the next engine leap. This roadmap aligns with continued investment in the Dreamliner for long-haul demand, not a shrunken derivative, while Boeing stabilizes narrowbody production and quality in the near term.

Bottom Line: Right Airplane, Wrong Mission

A true 737/757 replacement must be light, fast-turning, and gate-friendly with economics tuned to short- and medium-haul missions. The Dreamliner, designed for long-haul range and widebody comfort, starts with the wrong trade-offs. Boeing’s own experience with the 787-3 proves the point, and its public timeline for a genuinely new jet confirms the next move won’t be a 787 shrink. Expect Boeing’s eventual 737 successor to be a clean-sheet design paced by new engine technology—and expect the Dreamliner to remain where it excels: long-haul flying.

Time Will Tell When the A322 or 797 Will Take Flight

Whether it’s Airbus’s notional A322 or Boeing’s long-discussed “797” midsize jet, the question of feasibility ultimately comes down to timing, technology, and market appetite—and whether revolutionary concepts like blended-wing airframes will disrupt the familiar tube-and-wing design by the 2030s. Both manufacturers have the technical expertise to build a high-capacity, long-range single-aisle aircraft, but the economics are far more complex: development costs run into the billions, engine technology is still maturing, and airline demand in the middle of the market remains fragmented. Airbus could incrementally stretch the A321 platform into something like an A322, but even that would require a new wing, landing gear, and certification program.

Boeing would likely need a clean-sheet design to deliver the performance leap it has promised. Until propulsion advances such as open-fan engines and lighter composite structures are commercially ready in the mid-2030s, both concepts are likely to stay on the drawing board. In short, an A322 or a Boeing 797-style aircraft is technically possible but strategically premature—an appealing vision whose launch depends on aligning market demand, propulsion breakthroughs, and manufacturer risk tolerance.

Related News: https://airguide.info/?s=airbus, https://airguide.info/?s=boeing

Sources: AirGuide Business airguide.info, bing.com, Aviation Week, HeraldNet, Simple Flying, seattletimes.com