Everything you need to know about Monkeypox and travelling safely this summer

After two years of restrictions, infections and yo-yo borders, the last thing anyone wants is another public health crisis.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) will meet next week to determine whether monkeypox – an ominous-sounding infection cropping up in dozens of countries – is a “global health emergency of international concern.”

Around 1,800 people have contracted the virus since April this year, with Europe accounting for 85 per cent of these cases.

“Monkeypox will be opportunistic in its fight for survival, and its spread will depend on the conditions provided to it,” warned Dr. Hans Kluge, WHO’s European director.

Here’s what the new virus will mean for your summer holidays – and how you can protect yourself while travelling.

What is monkeypox and how dangerous is it?

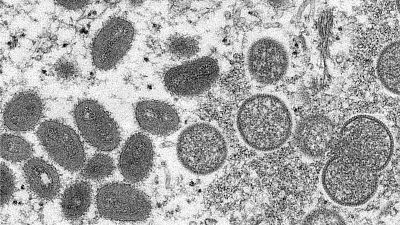

Monkeypox is a rare viral disease in the smallpox family. It is ‘zoonotic,’ meaning it originally spread to humans from animals.

There are two main variants of the virus: the milder west African strain (which is currently circulating) and the more severe central African strain. The milder variant has a mortality rate between 1 per cent and 3.6 per cent, but usually clears up on its own without causing serious illness.

There is no monkeypox vaccine, but a smallpox vaccine provides an 85 per cent protection rate against the new virus. Most people are not inoculated against smallpox, as it has been eliminated from the community – but many countries have purchased additional supplies of the vaccine in anticipation of more monkeypox cases.

What are the symptoms of monkeypox?

Initial monkeypox symptoms include fever, muscle aches, backache, swollen lymph nodes, headaches, chills and exhaustion.

The most obvious symptom – a chicken pox-like rash that spreads around the body – follows shortly afterwards.

Anyone who discovers an unusual rash or lesion on any part of their body should seek medical advice.

How does monkeypox spread?

Unlike COVID-19, monkeypox is not airborne. Instead, it spreads through close contact with an infected person. The virus can enter the body through broken skin or through the eyes, nose or mouth, and lingers on materials like clothing or bedding.

Most of the cases in the current outbreak have been sexually transmitted.

“So far in Europe, the majority – though not all – of reported patients, have been among men who have sex with men. Many – but not all patients – report multiple and sometimes anonymous sexual partners,” Dr Kluge explains.

“But – and this is important – we must remember that the monkeypox virus is not in itself attached to any specific group. Stigmatising certain populations undermines the public health response.”

You can also catch monkeypox if you are bitten by or eat the flesh of an infected animal. Despite its name, the virus is more common in squirrels and rodents than it is in monkeys.

Will monkeypox cause travel disruptions?

The WHO warns that summer events – like music festivals, pride events, and ‘spontaneous touristic gatherings’ – could accelerate the spread of the virus.

The risk is increased where young, sexually active people gather in large numbers. In May, the Spanish ‘Gran Canaria pride festival’ attended by 80,000 people spawned several cases.

However, this is not a reason to cancel such events, Dr Kluge insists. Instead, organisers should use them to raise awareness about the disease.

“Venue closure or event cancellation does not reduce sexual contact but rather shifts the activities to other settings, including private parties, which are less accessible to community outreach or public health interventions,” he continues.

At this stage, monkeypox is unlikely to cause mass cancellations or border closures.

However, your travel plans could be disrupted if you catch the virus while travelling, as the WHO recommends isolating until symptoms have completely disappeared.

Some countries – like Belgium – have mandated a 21-day quarantine for positive cases.

How can you avoid catching monkeypox while travelling?

At the moment, there is no reason to cancel your summer plans. The risk of widespread infection is low, claims the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA).

But there are ways to minimise the chances you get sick. Practising good hygiene and safe sex are the two most effective ways to do this.

While travelling, staying clean and being careful about who you’re in close contact with will minimise your chances of getting ill. The WHO recommends regularly washing hands, using hand sanitiser and avoiding large crowds where possible.

Though not all countries have released travel guidelines regarding monkeypox, the American Centre for Disease Control recommends travellers also exercise caution around animals.

“Don’t touch live or dead wild animals. Do not touch or eat products that come from wild animals. Avoid touching materials, such as bedding, that have been used by animals,” the advice reads.