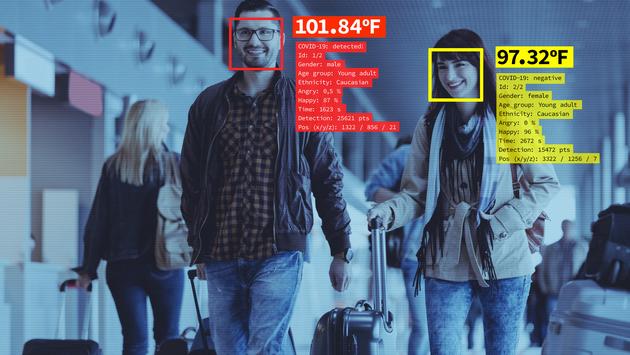

Facial Recognition Technology Used at US Airports Raises Concerns

In a move to expedite identity checks at airport security checkpoints, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) has initiated a pilot project involving facial recognition technology at multiple airports across the United States. By simply inserting their ID card into a slot and looking into a camera, passengers can now complete the identification process without physically handing over their documents to an officer.

The primary objective of this TSA pilot is to assist officers in verifying travelers’ identities more efficiently. Jason Lim, the TSA’s identity management capabilities manager, explained during a recent demonstration at Baltimore-Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport that the technology aims to confirm passengers’ self-claimed identities.

As technology continues to play an increasingly significant role in enhancing security measures and streamlining procedures, the TSA emphasizes that participation in the pilot project is voluntary and accurate. However, critics have expressed concerns regarding potential biases in facial recognition algorithms and the implications of data usage.

Facial recognition technology is currently implemented in 16 airports across the US, including Reagan National, Atlanta, Boston, Dallas, Denver, Detroit, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Miami, Orlando, Phoenix, Salt Lake City, San Jose, and Gulfport-Biloxi and Jackson in Mississippi. It is important to note that not every TSA checkpoint at these airports utilizes this technology, so not all travelers will encounter it.

The process involves travelers inserting their driver’s license into a card reader or placing their passport photo against a card reader. Subsequently, they look into a camera that captures their image and compares it to their ID, ensuring that the individual matches their presented identification. Despite the technology’s presence, TSA officers remain present and must authorize the screening.

To inform passengers about the pilot program, small signs are displayed, notifying them that their photo will be taken. The signs also provide a QR code for further information and indicate the option to opt out.

The utilization of facial recognition technology has raised significant controversy since its introduction. Elected officials and privacy advocates have scrutinized the TSA pilot, as they believe that increased biometric surveillance by the government poses risks to civil liberties and privacy rights. Concerns have been raised about the collection and access to biometric data, as well as the potential for malicious hacking into government systems.

Critics, including Meg Foster from Georgetown University’s Centre on Privacy and Technology, argue that facial recognition algorithms may display biases, particularly in recognizing faces of minorities. Furthermore, the potential for future storage of biometric data and the burden placed on passengers who wish to opt out are areas of concern. Passengers may fear that objecting to face recognition might raise further suspicion against them.

Jeramie Scott from the Electronic Privacy Information Center suggests that while participation is currently voluntary, it may become mandatory in the future. TSA Administrator David Pekoske has indicated that the use of biometrics could eventually become necessary due to its effectiveness and efficiency, although no specific timeline has been provided. Scott advocates for either complete avoidance of the technology by the TSA or an independent audit to ensure that it does not disproportionately affect certain groups and that images are promptly deleted.

The TSA contends that the pilot program aims to improve identity verification accuracy without impeding the speed of passenger flow through checkpoints, a critical concern for an agency processing 2.4 million passengers daily. According to the TSA, preliminary results indicate no discernible differences in the algorithm’s recognition capabilities based on age, gender, race, or ethnicity.

Jason Lim reassures the public that the images are not compiled into a database, and both photos and IDs are deleted. As an assessment, some data is collected and shared with the Department of Homeland Security’s Science and Technology Directorate in specific cases. However, the TSA assures that this data is deleted within 24 months.

Lim emphasizes that the camera only activates when a person inserts their ID card, ensuring that random images of individuals at the airport are not captured. This provides passengers with control over their choice to participate in the process. He also highlights that research demonstrates varying levels of accuracy among different facial recognition algorithms, with the TSA utilizing a high-quality algorithm for enhanced precision. The use of top-tier cameras is also a contributing factor.

Acknowledging privacy concerns and civil rights issues, Lim affirms the TSA’s commitment to addressing them, given the agency’s substantial daily interactions with the public.

Keith Jeffries, a retired TSA official, acknowledges the accelerated deployment of touchless technology during the pandemic. He envisions a future where a passenger’s face could serve multiple purposes, such as checking bags, passing through security checkpoints, and boarding the plane, without the need for boarding cards or ID documents. While he recognizes the existing privacy concerns and distrust surrounding biometric data provided to the federal government, he points out that biometrics have already become deeply integrated into society through privately owned technology.

It is clear that facial recognition technology at US airports remains a subject of significant debate, with privacy advocates and officials raising valid concerns about potential biases, data storage, and passenger choice. As the TSA pilot continues, it is crucial to strike a balance between improving security measures and respecting individuals’ privacy and civil liberties.