How airlines have managed their fleet mix during the COVID-19 pandemic

Flightradar24 note: ICF used Flightradar24 data to explore how airlines have managed their fleets during the COVID-19 pandemic and what that might mean for future fleets as demand returns.

In the past five years, the prevailing conditions created an environment considered by many to be as good as it gets for the aircraft market. Sustained traffic growth, low fuel prices, delays to new program deliveries, and unprecedented availability of finance—compounded by the grounding of the 737 MAX—has enabled many older narrowbody aircraft to remain in operation.

With demand for narrowbody aircraft often exceeding supply, aircraft manufacturers were preparing for further record-breaking delivery volumes over the next few years. Conversely, widebody programs were already seeing signs of oversupply, with delivery rates slowing whilst large and aging programs were preparing to head into retirement.

Fast forward to today and COVID-19 has plunged short term aircraft demand to record lows with airlines grounding most of their fleets. ICF has published its forecast for a phased demand recovery, returning to 2019 levels between 2023 and 2025. Whilst some regions will recover quicker than others, it remains clear that significantly less capacity will be required than had been anticipated in the next few years.

ICF has analysed Flightradar24’s aircraft tracking data alongside other industry sources to better understand how airlines decide which aircraft meet their reduced capacity needs, and the implications this may have for the global fleet in the coming years.

Current Trends

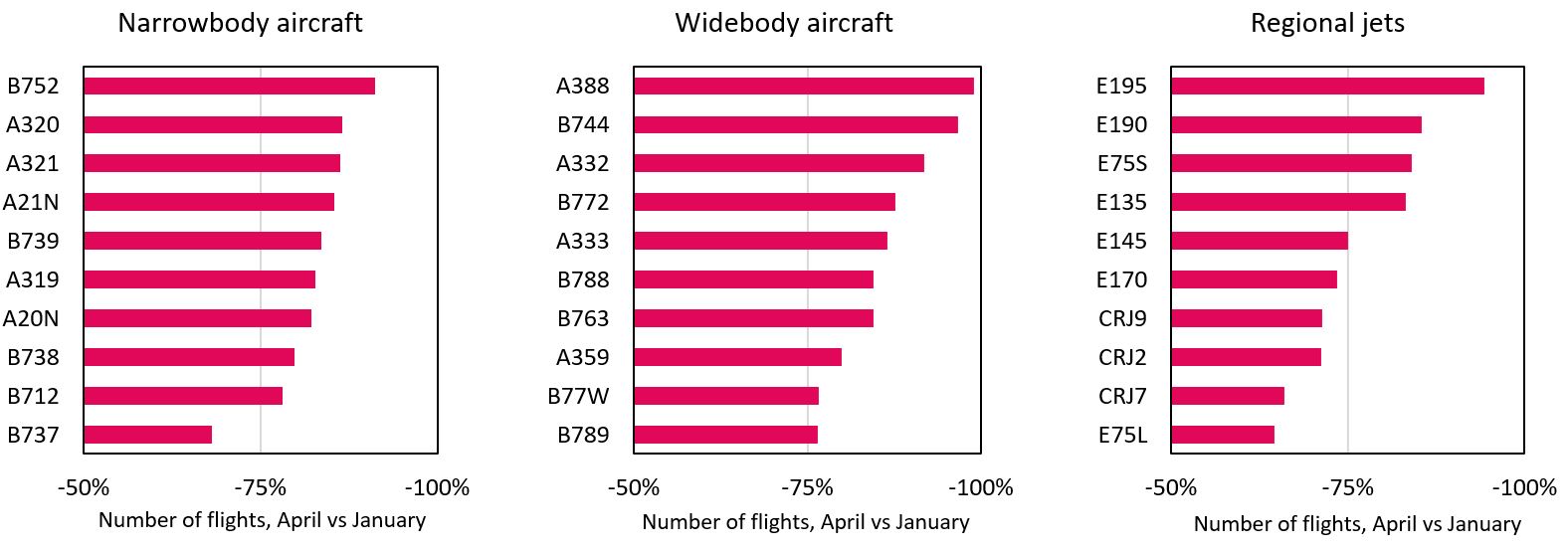

To understand the global trends of aircraft use, we looked at narrowbody, widebody and regional jets, focusing on the ten most common passenger aircraft in each category in the Flightradar24 data in January and compared them with April 2020.

On a global level, the number of aircraft in the sky declined 80% between January and April this year, with a variation of between 55% and 99% depending on the aircraft type.

Regarding narrowbody aircraft, even though the Airbus A320 and Boeing 737 families dominated the skies in April, they still declined by 82% on average. The activity of the two most common aircraft in January – Boeing 737-800 and Airbus A320 – dropped from nearly 600,000 monthly flights to about 100,000, while Boeing 757-200 experienced the largest relative drop from 20,000 flights down to just 1,800 flights.

Widebody aircraft have been impacted more than narrowbody aircraft, with flight activity declining 85% between January and April. The Airbus A380 has been most heavily impacted, decreasing from 10,600 flights in January to just over 100 flights in April. Boeing’s 787s and Airbus’ A350 experienced smaller drops of 78% on average, whilst flight activity of their newer and larger variants (Boeing 787-10, A350-1000) decreased by around 60%. Boeing’s B777-300ER, the second most common widebody aircraft in January, is also among those with the smallest drop in utilization, partly due to many airlines opting to use them as temporary freighters.

Regional jets experienced the smallest drop in utilization out of the three aircraft size categories at just 75%, likely reflective of the smaller domestic markets being less impacted during the current crisis. The larger regional jet Embraer E195 decreased the most (95%) while the smaller jets Embraer E175 and Bombardier CRJ-700, both with seating capacity of 70-80 passengers, dropped the least, with utilization only down by 65%.

Driving the decision making process

During more normal times, airlines typically use a fleet allocation model to optimally deploy their aircraft across their route network. The purpose of this is to optimize the supply / demand balance in order to maximize network contribution and profits.

Currently, with such a large share of global fleets grounded, each airline has an abundance of options for aircraft to fly their skeleton schedules. Driving their decision-making process will be several key factors, namely:

- Capacity: With demand drastically reduced, and carriers reporting weak load factors, airlines often operate their smaller sized aircraft across their network.

- Variable costs: Whilst tracking profitability is key, airlines also keep a close eye on ‘contribution’. This relates to the amount of revenue remaining after the variable flying costs (e.g. fuel, airport charges, navigation etc.) have been incurred. Modern aircraft such as the Airbus A350 and Boeing 787 families offer considerably lower variable costs when compared to previous generation aircraft.

- Cargo: This has become an ever more important revenue stream, either to supplement the reduced passenger loads on scheduled services or for airlines to operate ‘cargo only’ flights on their passenger aircraft fleets. The next generation widebodies offer improved cargo capabilities, for example the larger variants of the A350 and 787 can carry over 40 containers[1] which is on par with larger aircraft such as the 77W and significantly more than aircraft such as the 747.

Aircraft in service

Aircraft utilization is normally tracked closely to ensure airlines are maximizing the use of their assets and to reduce costs, however with much of their fleets grounded and parked in long term storage, they need to decide what proportion of their fleet to keep active in order to deliver the reduced flying program. ICF has examined the operating patterns for a couple of major carriers to determine the balance between utilization, commercial, operational and maintenance requirements.

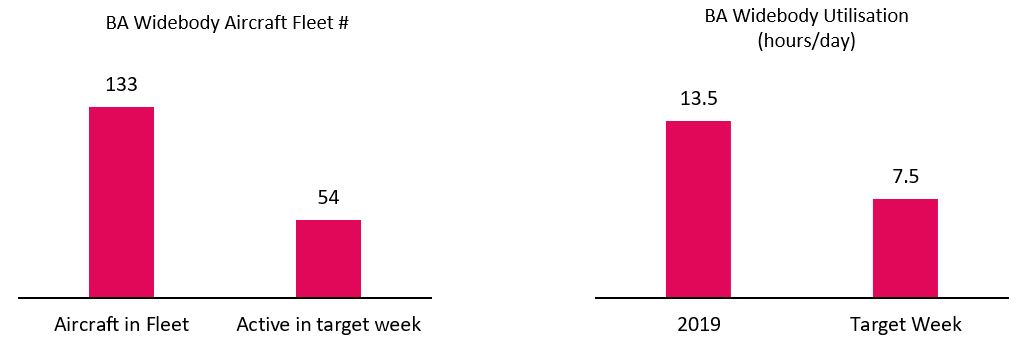

Firstly, British Airways (BA) currently has very limited short haul flying. However, they have been maintaining a degree of long-haul connectivity for passenger & cargo only flights. Typically, BA would operate more than 200 widebody flights per day, but in the last week of April, our analysis found BA operated less than 25% of this, reflecting an average of just 45 flights per day.

Normally BA’s long-haul fleet delivers more than 13 hours of utilization each day, equivalent to 10,500 km per aircraft per day. The British flag carrier would have required less than 30 widebody aircraft if BA had maintained these levels of utilization. However, BA has kept over 50 widebodies flying with utilization levels averaging 7.5 hours per day. In other words, BA is choosing to operate with 1.6x the number of widebody aircraft than it typically ‘needs’. This is likely explained by a combination of factors, such as the new schedules, longer turns required for either cleaning or cargo handling, and maintaining a ‘buffer’ to enable additional flights to be added relatively easily since taking aircraft out of long-term storage can take some time.

A similar analysis for Delta Air Lines (DL) with over 800 aircraft available implies a similar pattern. Delta is operating a relatively limited widebody schedule averaging just over 20 flights per day and, like BA, choosing to keep at least 2.5x aircraft in operation for 1x worth of widebody flying. Across their narrowbody fleet 300 aircraft were operated in the target week with 200 being operated on any given day, again at reduced levels of utilization.

Some aircraft will not return to service

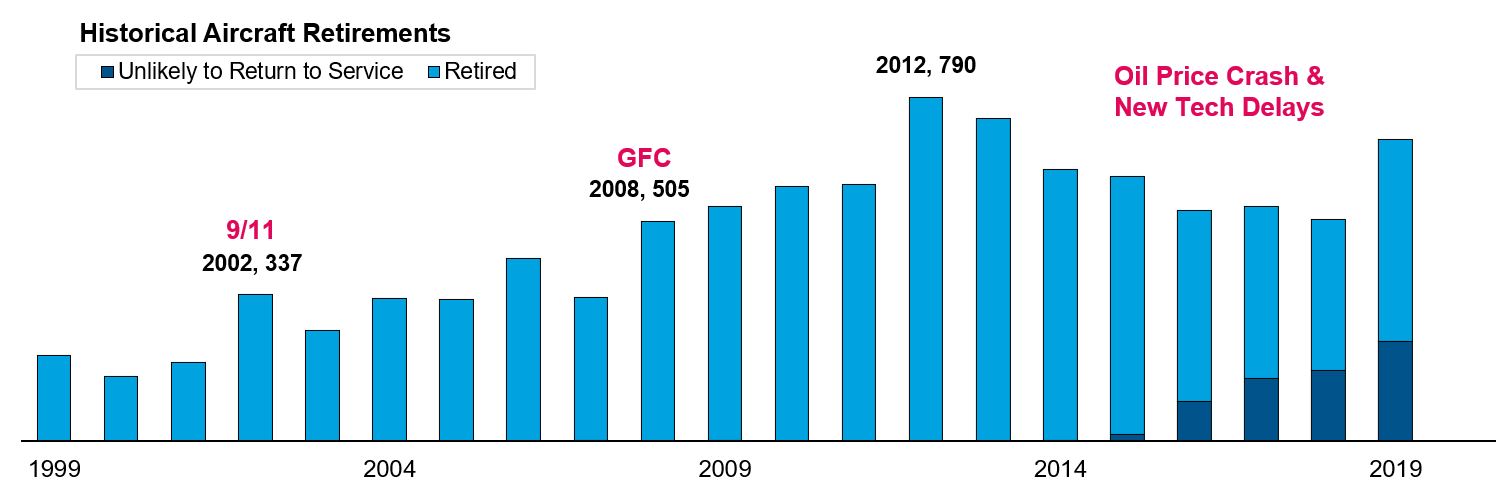

Historically, traffic downturns have triggered accelerations in scheduled retirements and the freezing of production rate increases by OEMs. During this time, excess capacity (i.e. aircraft) typically enters storage, and a share of which is permanently withdrawn from service in the following years. COVID-19 has already accelerated the timeline of scheduled retirements and OEMs have cut production rates by around 30%.

Accelerating retirements

During April and May 2020, many airlines announced accelerated retirement plans for parts of their fleets. Although four-engine aircraft have been gradually retired in favor of twin-engine aircraft over the last few years, COVID-19 is accelerating this transition. For example, the Boeing 747 is continuing to disappear from the skies, with Corsair, KLM, Qantas and Virgin Atlantic announcing the early retirement of this model. Twin-engine widebodies exposed to early retirements are the A300, A310, 767 passenger aircraft, and older A330 and Boeing 777s. The retirement of previous generation narrowbody aircraft that some airlines planned to slowly phase are also being accelerated. Airlines such as Air Canada, American Airlines, Austrian, Delta, and Singapore Airlines announced that they will retire old A320ceo, 737 Classic and NG, 757, MD-80 and MD-90 aircraft.

Future aircraft mix provides some positive news

ICF have considered a ‘basket’ of global airlines (American, Air France, Delta, Qantas, Virgin and KLM) to consider the likely reduction in CO2 emissions arising through their accelerated fleet retirement programs.

The result of this is that emissions per flight and per seat are expected to decrease by -2.2% and -2.6% respectively. Within this group, Virgin Atlantic is expected to decrease the most (by over 10% on a per seat and flight basis) owing to the withdrawal of its four-engine fleet of Boeing 747 and A340 aircraft.

For comparison these savings are equivalent to 3-4 years of ongoing industry wide levels of fuel efficiency improvements. Whilst there remains uncertainty as to how and when demand will start to return, it is at least clear that the aircraft returning to service will typically be on average more fuel efficient and offer lower carbon emissions on a like for like basis.