How do pilots stay current in a pandemic?

With demand for air travel still far below normal levels thanks to COVID-19, airlines are having to juggle a number of difficult decisions and manage not only the financial pain but also the logistical chaos that comes from suddenly cutting flights and parking planes. One of those logistical issues is that of pilot currency.

Pilot currency requirements are the rules that state how much flying and recurrent training a pilot has to complete in a given timeframe in order to be legally allowed to operate a commercial aircraft with passengers. They are generally set by aviation authorities, and although there is some variation across the world, FAA requirements in the US tend to be a benchmark – so we’ll focus especially on those.

Normally the requirements aren’t difficult to meet. In this unprecedented situation, however, there are thousands of pilots finding that they can’t even maintain the bare minimum. And that means later on when things hopefully bounce back, they’ll need more extensive retraining and checks before they can return to the controls of a commercial flight. As the number of pilots in that situation stacks up, a backlog is growing for pilots that intend to return to flying in the coming months.

So, what are the requirements?

How to stay current

One aspect in particular is central to pilot currency. In order to maintain currency on a given aircraft type and fly it while carrying passengers, a pilot needs to have performed three takeoffs and landings within the previous 90 days. On a normal pilot’s schedule, fulfilling that isn’t even a question. But nowadays there are hundreds of pilots who have taken time off. Many of them already haven’t flown for over 90 days.

“I don’t fly at all!” says Captain Mat Bandelow, when I asked him what his schedule was looking like these days. Bandelow is a captain at a US regional carrier (he asked that it not be named) who has over 11,000 hours logged, and has been a captain on the Embraer 175 for over 8 years. He took a voluntary leave offer back in March that now looks set to continue until the end of September.

“Our company and the union have worked together really well, pleasantly so. They worked together to come up with a voluntary leave that means I’m on three-quarter pay. I’m in an economic situation where I can survive on that,” Bandelow goes on. “I was furloughed from my first company, and it was just under a year into my aviation career. I was all giddy with excitement getting to fly and then to get furloughed was devastating. So the reason for me taking the leave I’m on other than the fact that I could do it financially was that if my taking the leave keeps a younger guy from getting furloughed, at least temporarily, then I was gonna do it. That’s what motivated me. And I’m fully expecting to go back to work come October.”

Bandelow says that getting his required takeoffs and landing in this case wasn’t feasible, because he would have had to rent an aircraft and go do it on his own. With the situation as it is now at most airlines, trying to cycle through all temporarily grounded pilots to make sure they stayed current wasn’t feasible.

Annual training

There’s also the matter of a pilot’s annual training – what’s often known as CQ, for continuous qualification. That normally needs to happen every 12 months for a pilot to maintain currency, but when the pandemic hit, many pilots missed theirs or had to delay them. Because training centers closed, the FAA even instituted a grace period allowing pilots extra time to complete their annual training. But for Bandelow, even that grace period won’t be enough.

“I was due for my annual training anyway about two months after COVID hit. So I’m basically going to have to pick up kind of where I left off, go through my annual training and get re-signed off. But I will have to do extra training. I can’t just sit in the SIM for a few hours and they bless me and off I go,” says Bandelow. “That means I’ll be out flying with a check airman. It might be an entire week. Then when the check airman says you’re good to go, you’re good to go.”

Bandelow says that means he’ll do two days of checks in the simulator at a training facility, and then he’ll go out to fly passengers. While he does that, though, he’ll be undergoing what’s known as a line check. Because he’s a Captain he’ll sit in the left seat as usual, but a check airman—a senior pilot in charge of signing off pilots on the aircraft type—will sit in the right seat and have ultimate command over the aircraft. That’s not because the airline has any particular doubts about his ability to be the pilot-in-command (PIC). Rather it’s part of the stringent requirements in place to make extra sure that anyone in command of an aircraft is definitively up to the task.

“It’s almost like being a new hire where they have to make sure that you’re not an idiot still,” says Bandelow. “Normally we might fly a couple of legs with a check airman monitoring everything we do from the jumpseat. But in this case it’s essentially repeating what I had to go through when I first became a captain. I’ll find out exactly how long the process will be as I get a little bit closer.”

Can you forget how to fly?

I asked Bandelow if he’s worried that after six months, he may have forgotten a thing or two. Or is flying an E-jet like riding a bike?

“Of course it will have been a full six months that I haven’t been behind the controls of an aircraft. That’ll be the longest period of time since I started flying. So for me this is extraordinary,” says Bandelow. “But I’ve been flying the 175s for over ten years, so yes the body will remember. Although I fully welcome the extra check and training. I don’t want to go out there assuming that I’m good. I want to be the best I can for my passengers.”

Some pilots have stayed busy

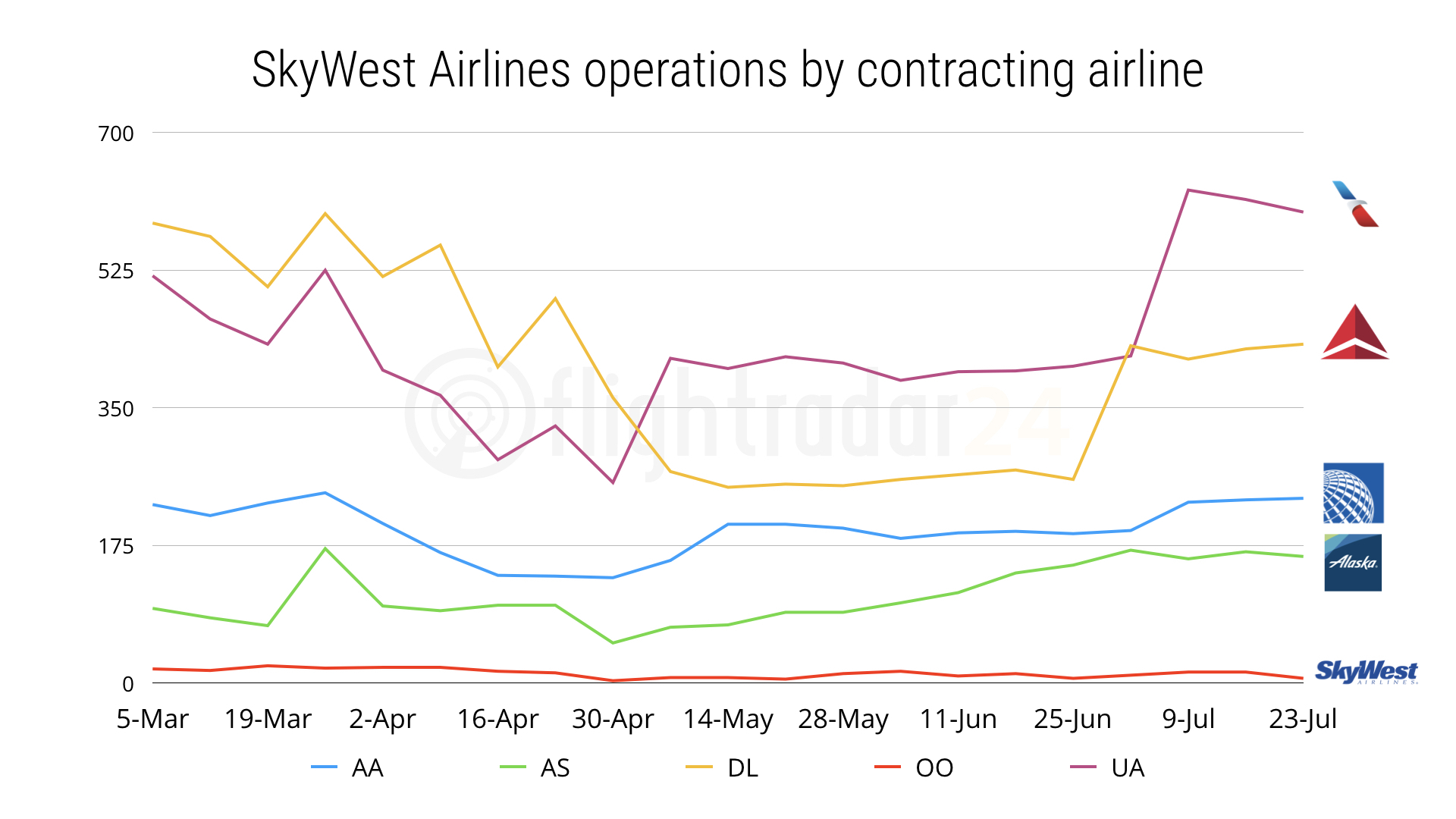

Veronika Bensova just started flying with Skywest (dedicated to Delta’s regional flights) last year, after moving over from flying Cessna 208EX Grand Caravans for Mokulele in Hawaii. She was LaGuardia (LGA)-based with Skywest, but when COVID-19 hit and things got shuffled around, she was transferred to the Minneapolis (MSP) base. She says she’s been fortunate and has been able to keep flying throughout the height of the pandemic, averaging 70 hours a month. Before COVID she would typically do around 100 hours a month. That means she hasn’t had to contend with any currency issues.

That’s partly thanks to the fact that roughly 1400 Skywest pilots (out of around 5000 total) took that company’s voluntary time off deal, so although flights have been heavily reduced, many of those who wanted to keep flying did. But she hasn’t been spared all of the complications when it comes to currency.

“I was supposed to get my CQ [continuous qualification], which you get every 12 months, in May,” says Bensova. “You do maneuver validations, emergency procedures. You have to fly an approach. You do one day ground school and three SIM sessions, and then you have a little check ride, also in the SIM, on day 4. Just to keep you current. The training department was backed up, so they moved it. You have a grace period now, so what the FAA did was they extended it up to 60 days. That means I have to go for my training in September.”

She’s hoping that will happen as planned, because as things stand she would go out of currency if it got pushed any further. And there are many pilots in her position. The training department only reopened a few weeks ago, after being closed for months. “Now they’re all backed up with the people who were previously supposed to go,” says Bensova. “Imagine the number of people that need to get their CQ done right now. They’re totally saturated.”

Medical clearance

Part of maintaining currency is getting an annual medical clearance. Extensions have also been granted for medical checks because even if doctors’ offices were open these past months, many pilots preferred to avoid going to one in light of the circumstances. But catching up on medical checks is a much less complicated matter than trying to funnel everyone through training before their qualifications expire.

Airlines have been making attempts to keep pilots current even if they’ve been on reserve, whenever they can. Bensova says that can cause some disruption to pilot schedules. “I got displaced last month,” she explains. “I had a trip and they called me to displace me from that trip because someone needed landing currency. As the pilot you’re actually supposed to keep an eye on it, and say hey I’m about to lose my currency on the landing. So they call crew support, and scheduling will kick out a pilot to make room for them to get their landings. That was me in this case.”

She’s happy to be flying, though, and happy to roll with the punches, she says. “I love flying the Embraer. And I love this job. I wouldn’t want to do anything else.”

Mat Bandelow is optimistic about the future, even with all the shake-ups. “Here in the States it’s still totally up in the air what’s going to happen but people travel,” he says. “We’re resilient. This is the biggest thing to happen ever to the industry, so a lot of people are unsure. Of course I am too. But I think we’re going to bounce back from this and people are going to start flying again. I’m pretty optimistic. I’d love to see people get comfortable with each other again, on airplanes, where just sitting next to someone isn’t the end of the world.”