Airlines need the Boeing 737-10 Max to replace older 757s

Boeing’s supportive hand from the US government came late in 2022. As important as this was for Boeing, it is also important for many more interested parties. The Boeing supply chain clearly is near the top of that list. However, there is also the rest of the industry that needs the duopoly back in balance. The market needs the 737-10 Max, the largest 737 Max.

The 757 was primarily a US airline workhorse: American, Delta, and United were the largest users. There were 625 Boeing 757 aircraft in service as of December 2020, comprising 572 757-200s and 53 757-300s.

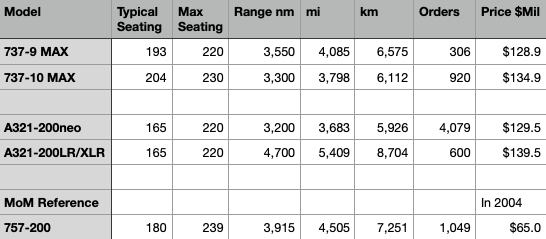

New markets are maturing that need the MoM. The middle of the market, often abbreviated MoM, is the airliner market between the narrowbody and the widebody aircraft, a market segmentation used by Boeing Commercial Airplanes since at least 2003. Both Airbus and Boeing produce aircraft that serve this segment. The model referenced for this market is often the Boeing 757-200, last produced in 2004.

But the world has changed. This is not because the Airbus brand is especially attractive. The biggest driver is more likely that Airbus has the right-sized product that ticks the most boxes.

Fleet planning is a long-term decision process. The MAX grounding slowed down the progress Boeing needed to offer a competitive aircraft. The market could not wait – commercial aviation is risk averse, and going through the pandemic and pilot shortage, choices had to be made and fast. Airbus got the nod by default.

China and India face the same problems as other markets – growing traffic and a pilot shortage. You need larger single-aisle airplanes to move the traffic. Note also the rise of the EU and Turkey as MoM markets. There are several markets popping up – and each of these could just as easily have bought a 737-10 Max. If it were available.

Here’s another perspective. Starting with January 2021 and going through January 7, 2023, the percentage of single-aisle deliveries that meet the MoM definition is 33% or better. That was not the case during the 757 era. For Airbus, this is the A321 and for Boeing, we include the 737-9 Max and will also include the 737-10 Max when it starts being delivered.

The market has changed – Airbus and Boeing have been successful with their upsizing strategies. Airbus was fortunate to benefit more from this than Boeing up to now.

Boeing no doubt made the case to people like Senator Cantwell and others that the need for an extension for the MAX certification was necessary. They likely brought supportive materials from MAX 7 and MAX 10 customers. The decision to give Boeing the extra time is rational from the perspective of the OEM. But even customers have stated they all want a common flight deck because pilot training is expensive and, frankly pilots perform a lot of their work from “muscle memory”. You don’t want pilots confused under any circumstances. Keeping the flight decks common is a common-sense safety issue. This is why the changes required will also be retrofitted to current in-service MAXs.

At this writing, Airbus deliveries for 2023 are five A320neos and five A321neos. For Boeing four MAX 8s and one MAX 9. The playing field is tilted in Airbus’ favor and that is because of Boeing’s decisions made several years ago. There is no point in finger-pointing. We are where we are. The important point is that Boeing is working to restore the duopoly balance and has been given a hand. Customers ordered the MAX 10 in droves (over 600) making it the second most popular model in the MAX family. The US government got the message and offered Boeing more time. Now it is up to Boeing to show it is worth this support and get the two remaining MAX models certified and delivered.